MFH Home

Family Trees

Records

Wills

MIs

Studies

Memories

People

Places

Related Families

Odds & Ends

Mail David

Child Death

in a Yeoman Family: A Social Study

An

examination of the numbers of child deaths, within each family group of

the MAYs, reveals that nearly every family lost between one and two

children in fancy across the whole period of study. The percentage of

infant deaths is shown below (fig,7), taken at

face value, is misleading. The low percentages of the early and late

generations are due to lack of information. In the early period, there is

a lack of of records: many children are known only from their parents’

wills, by which time they had already outlived infancy. The last

generation under study contains two families (those of James MAY

(1760-1805) of Englefield and John MAY (1775-1866) of Sindlesham) with

several years between births of children. Thus, there may have been

miscarriages or still-births in these years which would increase the

percentage.

Fig.

7. Table showing Infant Mortality in the MAY Family

|

Generation |

Average

Infant Mortality Rate |

Average

Number of Child Deaths |

|

1st

(born 1630-1650) |

0% |

0 |

|

2nd

(born 1651-1675) |

11% |

2 |

|

3rd

(born 1676-1700) |

20% |

1 |

|

4th

(born 1701-1725) |

21% |

2 |

|

5th

(born 1726-1752) |

15% |

1 |

|

6th

(born1753-1789) |

18% |

1 |

|

7th

(born 1790-1830) |

0% |

0 |

The

increased percentage of infant deaths in the third and fourth generations

illustrates an interesting point. The figures are raised by the 40%

mortality rate of the children of Charles MAY (1656-1697) of Reading and

the 43% rate of the children of Charles MAY (1670-1714) of Basingstoke.

Both these men lived within towns, where living conditions were generally

poorer than on the country farms where the rest of the family lived. Disease

was more common in town and spread quicker and more easily. Charles MAY

was wealthier than his contemporaries, but this could not prevent three of

his children dying of smallpox between 1708 and 1718. The fact that wealth

did not necessarily help small children to survive is echoed in the

countryside where mortality of MAY infants was broadly similar per family.

It was the difference between town and country life which effected this

most; though the situation may have improved by the early nineteenth

century, when none of Charles MAY (1767-1844) of Basingstoke’s urban

children died in infancy. Of course, all the MAYs under discussion were

reasonably well off and, though there is no appreciable difference between

the infant mortality rate of yeoman and gentry families, if some of the

family had been agricultural labourers or industrial workers, the rate may

have been much higher.

It

is difficult to assess the attitudes of the MAY family towards children,

and infant deaths in particular, as there are no existing personal records

such as diaries or letters which can be examined for the period of study.

There is only Mary Anne MAY (1848-1931)’s reference to her grandfather,

Daniel MAY (1771-1851) being “devoted to his sons and a most kind and

liberal father” (May 1916). Repetition of names of dead children

among those born later may indicate some detachment from the children, but

this was a common practice. In the MAY family, in the seventeenth and

first quarter of the eighteenth century, every child who died young had

their name reused amongst any siblings which followed. Only from about

1725 onwards do deceased children begin to keep their individuality.

Though Charles MAY Junior of Basingstoke (1800-1841)’s

youngest daughter became Jane after her sister Jane Simonds MAY, William MAY

(1709-1777 of

Bramley’s youngest son was not named after his deceased brother, Thomas,

in 1752; James MAY (1728-1772) of Englefield did not name any of his

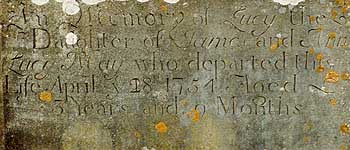

children Lucy Ann after his deceased eldest daughter (1754)(1); and

Thomas MAY (1737-1800) of Brimpton’s youngest daughter (b.1783) did not

become ‘Jane’ after her sister who had died three years before. It is

interesting that the loss of the latter two children was felt so great

that memorial gravestones were erected to them, yet they were only three

and two years old respectively. This also happened with John, the young

son of William MAY (1729-1797)

of Burghfield. Similarly, in 1714, Charles MAY (1670-1714) of

Basingstoke’s three young children had been remembered on his own and

another memorial plaque. Perhaps if he had lived to have further children,

their names would not have been re-used. Certainly, the MAYs seem to have

felt great sorrow at the loss of their children from the late eighteenth

century, and probably as early as 1700.

It

is difficult to assess the attitudes of the MAY family towards children,

and infant deaths in particular, as there are no existing personal records

such as diaries or letters which can be examined for the period of study.

There is only Mary Anne MAY (1848-1931)’s reference to her grandfather,

Daniel MAY (1771-1851) being “devoted to his sons and a most kind and

liberal father” (May 1916). Repetition of names of dead children

among those born later may indicate some detachment from the children, but

this was a common practice. In the MAY family, in the seventeenth and

first quarter of the eighteenth century, every child who died young had

their name reused amongst any siblings which followed. Only from about

1725 onwards do deceased children begin to keep their individuality.

Though Charles MAY Junior of Basingstoke (1800-1841)’s

youngest daughter became Jane after her sister Jane Simonds MAY, William MAY

(1709-1777 of

Bramley’s youngest son was not named after his deceased brother, Thomas,

in 1752; James MAY (1728-1772) of Englefield did not name any of his

children Lucy Ann after his deceased eldest daughter (1754)(1); and

Thomas MAY (1737-1800) of Brimpton’s youngest daughter (b.1783) did not

become ‘Jane’ after her sister who had died three years before. It is

interesting that the loss of the latter two children was felt so great

that memorial gravestones were erected to them, yet they were only three

and two years old respectively. This also happened with John, the young

son of William MAY (1729-1797)

of Burghfield. Similarly, in 1714, Charles MAY (1670-1714) of

Basingstoke’s three young children had been remembered on his own and

another memorial plaque. Perhaps if he had lived to have further children,

their names would not have been re-used. Certainly, the MAYs seem to have

felt great sorrow at the loss of their children from the late eighteenth

century, and probably as early as 1700.